Dark like me, that is my Dream!

Black Musicality and Cultural Forms in Langston Hughes' "The Weary Blues"

Langston Hughes’ collection The Weary Blues (1926) commences with the lamenting of a bluesman at a Harlem bar, introducing the central motif of Black weariness through the display of escapism from sociopolitical inequalities. Written during the Harlem Renaissance, a period when blues, jazz, and cabaret served as modes of Black expression and escapism, Hughes infuses his poetry with this musical form to critique the sociopolitical complexities that constrained the average African American.

This is evident in the structural and thematic similarities between Hughes’ poem “The Weary Blues” and blues singer Henry Thomas’s “Texas Worried Blues,” as both use musical repetition and Black dialect to express a profound sorrow for the effects of systemic and cultural oppression. Through poems like “To Midnight Nan at Leroy’s” and “Jazzonia,” Hughes critiques the hyper-sexualization and commodification of Black life in Northern cities, while “The Jester” and “Aunt Sue’s Stories” serve as recanting Southern-rooted oral tradition and folklore to highlight the resilience within ancestral heritage. Across the pieces, Hughes resists attempts to erase or distort Black identity through his use of musicality, blues form, and regional nuances, authentically and free from the white gaze.

The Harlem Renaissance

During the Great Migration, cities like Chicago, Philadelphia, and New York attracted Black migrants seeking asylum from atrocities within the Jim Crow South. The influx of Black artists into New York encouraged the emergence of Harlem as the grounds of Black artistic expression and intellectual discourse (Trotter 31). Therefore, the Harlem Renaissance was the cultural explosion of Black artistic mediums, such as blues, jazz, literature, visual arts, and performance, representing the African American experience. Harlem, however, was far from the haven that Black creatives had expected, as it also became a spectacle for white patrons who were “merely looking for exotic thrills in the black community” (Davis 276). The generation of artists who emerged during the Renaissance centered African American culture as a means to offer representation to the populace underrepresented by American society through both subject and form, with Langston Hughes being one of them.

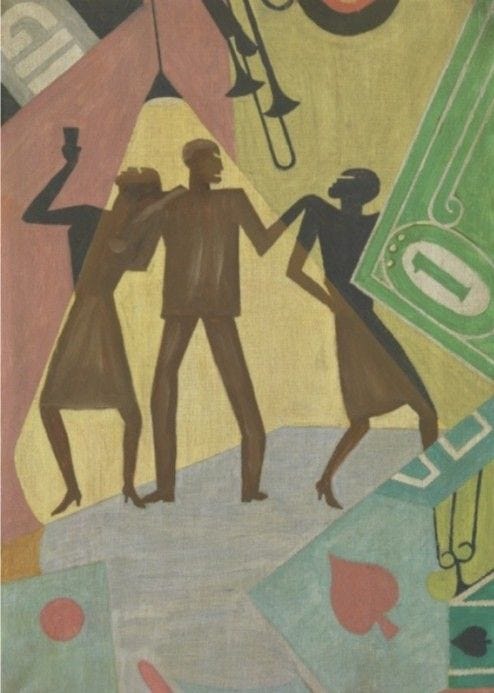

Among such artists were cabaret performers, singers and dancers alike, who gave Harlem’s nightlife a lustful appeal imperative enough to become an “important by-product of the new interest in the Negro created by the movement,” especially, one that “strongly influenced the early poetry of Langston Hughes” (Davis 276). Therefore, when the Black literary scene was still in its infancy, Hughes faced the challenge of capturing the Black experience without reducing its complexity or feeding into the voyeuristic gaze of the white majority.

To meet this challenge, Hughes turned to the authentic voices of Blues musicians, emulating their lyricism and structural patterns to cultivate a poetic voice unmistakably critical of American society through the Black lens. Critics argue that The Weary Blues reflected the “certain superficial elements of the New Negro Movement,” suggesting that Hughes may have unintentionally played into the aesthetics of the “New Negro exoticism,” and disengaged from the realities of Black life (Davis 278).

Such critics often overlook the communal and expressive nature of blues and jazz, which served as an emotional outlet and means of escapism for African Americans. Drawing directly from this tradition, Hughes's work did not sensationalize the evolution of Black art but gave new ways to express struggle and survival.

Musicality As Representation

By incorporating rhyme, repetition, and rhythm into his poetry, Langston Hughes transformed the traditional poetic structures into lyrical, second-person compositions deeply rooted in Black blues and jazz schematics. Hughes himself had believed that the poems modeled on Black music could “appeal as broadly and could serve Afro-Americans in the essentially positive ways he believed the music itself had” (Hansell 16). His emulation of the bluesmen's lived language and lyrical habits allowed him to craft poems similar to blues songs, demonstrated by “The Weary Blues'” resemblance to Henry Thomas’s “Texas Worried Blues” (Tracy 81).

Following the typical blues stanza of AAA then AAB, where the “first thought [is] repeated twice, the last word of which rhymes with the final word of the last line, which is a resolution,” “The Weary Blues” also contains a similar chordal progression of the typical twelve-bar blues song (C, F, and G chords), with four beats per bar (Tracy 80). Tracy’s comparative analysis of Henry Thomas’s “Texas Worried Blues” and Langston Hughes’s “The Weary Blues” further demonstrates the structural and thematic similarities between Hughes’s poetry and a bluesman’s song (see fig. 1).

Figure 1: Comparison of Hughes and Thomas’ Blues Work.

Thomas and Hughes use repetition and dialectical expressions to convey emotional despair and isolation. Thomas' “I’ve got the worried blues / God, I’m feelin’ bad” (Thomas) alongside Hughes’ “I got de weary blues / And I can’t be satisfied,” captures a similar melancholy born from an existential fatigue as a result of the matrimony between systemic oppression and inequalities (25-26). The use of the Black dialect in phrases like “God, I’m feelin’ bad” and “I ain’t happy no mo’” imbues the reader with the authenticity of the speaker, allowing them to be situated in a distinctly Black oral tradition critiquing the sociopolitical space while introducing severe depression as the by-product of oppression.

However, both speakers in each respective work view their death as a resolution and release from this weariness rather than the murder or subjugation of their oppressors. This further demonstrates that Hughes's “remarkable success with manipulating the formulaic quality of blues” is a testament to his deliberate embodiment of blues as a literary art form, which refused to erase the Black experience, suffering, and expression from literature (Tracy 81). Therefore, Hughes’s use of blues form was integral to his poetry, as it served as a mode of preservation, inscribing Black feeling into the literary canon.

Geographical Implications of Hughes' Poetry

In the section “The Weary Blues,” poems such as “To Midnight Nan at Leroy’s” and “Jazzonia,” Hughes portrays Harlem as lustrous and sensational to critique the over-sexualization of Black women while simultaneously emphasizing the challenge of transcending systemic oppression.

In “To Midnight Nan at Leroy’s,” Harlem nightlife breathes life into Black womanhood, laced with a “dangerous” freedom, as it grants Nan a desirous aura that exudes from her femininity. Even so, this same freedom renders her threatening within society’s eyes as it demands that Black women suppress their sexual agency to appeal more “palatable” for male companionship. Hughes’ depiction of Nan’s “shameless” (2,18) behavior is evident in her declaration of intimacy in the third stanza:

Sing your Blues song, Pretty baby. You want lovin’ And you don’t mean maybe (9-12).

The emotional intensity of blueswomen like Bessie Smith and Trixie Smith, who vocalized their desires for intimacy and fear of rejection. However, Hughes removes the illusory nature of Nan’s sensuality by introducing racialized exoticism by describing Harlem nightlife as a “Jungle night” (6) and Nan as a “jungle lover” which conjures the image of Nan’s sexuality as primitive, reflecting a more dangerous stereotype of Black female sexuality (13). Hughes opens and closes the poem with a refrain that mirrors the cyclical structure of a blues song, while highlighting the social entrapment Nan must endure:

Strut and wiggle, Shameless gal. Wouldn’t no good fellow Be your pal [man] (1-4; 17-20).

Therefore, Hughes presents society's response, both Black and white, to the same judgment, highlighting confinement during escapist activities.

A similar Harlem ambiance decorates “Jazzonia” as Hughes uses the bluesman’s framework to place the cabaret in a mythic space. Even with the magical atmosphere, there is a certain “strident and hectic quality, and there are overtones of weariness and despair” (Davis 277) that the “dancing girl whose eyes are bold” and the “six long-headed jazzers” must endure (Hughes 7). The girl with “bold” eyes and wearing “gold” while the jazzers are “long-headed” are verdicts of the depiction of black dancers in Harlem nightlife, caught between reverence and reduction. Hughes sharpens this critique by likening the dancing girl to Eve, “Were Eve’s eyes / In the first garden/ Just a bit too bold?” (9-11), and Cleopatra, “Was Cleopatra gorgeous / In a gown of gold?” (12-13).

Both women were punished for their beauty and desires, situating the Black woman performer within a stereotypical historical arc of gendered exile: Eve expelled from Eden for seeking knowledge, Cleopatra killed for her allure. Hughes is essentially arguing that there is a similar danger for Black women in Harlem, as some outside force will ultimately consume Black women's identity in a place that they use for escape.

Therefore, Hughes's use of the blues structure critiques the emotional and individual confinement in spaces meant for Black liberation. In the latter section, Hughes also demonstrates the emotional toll of surviving under the constant surveillance of oppression and how the answer relies on the reconnection with African Americans’ ancestral roots.

The poems in “The Negro Speaks of Rivers” differs from those in “The Weary Blues” as there is an emphasis on ancestral memory, which Hughes presents through folklore or oral storytelling. The also section leans further into the implications of Black generational trauma.

In “The Jester,” Hughes uses the Black folkloric figure of the trickster, a character who masks pain with humor as a means to juggle the dysfunctional lifestyle of oppression by invoking the “survival of the fittest” mentality (Ogunleye 443). As Hughes asserted, alongside blues and musicality, it was important that black artists “use folklore and folk life as professional musicians have used black folk music” (Tracy 78). Therefore, “The Jester” serves as a cultural metaphor for the emotional dexterity demanded of Black performers under white surveillance.

The speaker, consumed by his role as an entertainer, begins to disvalue his emotions, or even disengages with them, as a means to survive a system that demands a price for independence: “Tears are my laughter. / Laughter is my pain” (Hughes 35). Hughes' critique of a society that demands such a laborious task while treating the Black individual as expendable does not end there, but extends into a moment of hope by the end of the poem. The folklore surrounding the African King is that before enslavement, African Americans used to be rulers of the African lands. Thus, as the Jester questions, “Once I was wise. / Shall I be wise again?” Hughes presents a possible reclamation of self-worth and agency through cultural memory and ancestral knowledge (17-19).

This reclamation of self-worth and agency continues in “Aunt Sue’s Stories” as Hughes uses oral traditions as a form of resistance and healing to oppression and inequality. The act of storytelling passed intergenerationally is a transformative power that passes the resilience of ancestral knowledge while preserving it. Aunt Sue’s stories, coming from “right out of her own life,” are Hughes drawing attention to the cultural importance of resisting erasure; just as his utilization of blues, jazz, and folklore affirms Black identity, oral storytelling remains the foundation of Black culture (22). The “dark-faced child” who silently listens to Aunt Sue contrasts with the Jester’s loud performances, illustrating storytelling as an inheritance rather than a survival mechanism (Hughes 39). The child who listens, listens with an intensity and understanding of Aunt Sue’s lived experiences, wherein Hughes writes:

Black slaves Working in the hot sun, And black slaves Walking in the dewy night, And black slaves Singing sorrow songs on the banks of a mighty river (6-11).

The repetition of “black slaves” is the reemergence of the musical cadence hidden within black oral storytelling, which allows Hughes to further position the spiritual and cultural nuances of the Black diasporic identity on an evolving rotation through pain and power. The child’s silence demonstrates a way to ensure that the pain and survival of our ancestors are inherited, utilized, and not lost unintentionally.

Conclusion

Langston Hughes's The Weary Blues illustrates the multilayered complexity of Black identity. In using the blues as a narrative form, Hughes was allowed to reorient the lives of oppressed African Americans through recurrent situations within the typical African American’s life (Johnson and Farrell 59).

Though music and other cultural nuances within the Black community were depicted as powerless means of aiding “those who are already too deep in despair, or who, because of constitutional or spiritual deficiencies, are overwhelmed by the very means they choose to escape an oppressive and frightening reality,” Hughes demonstrates that keeping cultural nuances, musical traditions, historical memories, and a reclamation of agency within their art, African Americans can halt the process of erasure (Hansell 22). Maintaining these cultural nuances and symbols also creates space for Black expression, escaping society's exoticism and surveillant nature.

Works Cited

Davis, Arthur P. “The Harlem of Langston Hughes’ Poetry.” Phylon (1940-1956), vol. 13, no. 4, 1952, pp. 276–83, https://doi.org/10.2307/272559.

Hansell, William, H. “Black Music in the Poetry of Langston Hughes: Roots, Race, Release.” Obsidian, vol. 4, no. 3, 1978, pp. 16–38.

Hughes, Langston. The Weary Blues. 1926. Martino Fine Books, 2022, pp. 1–91.

Johnson, Patricia A., and Walter C. Farrell. “How Langston Hughes Used the Blues.” MELUS, vol. 6, no. 1, 1979, p. 55, https://doi.org/10.2307/467519.

Ogunleye, Tolagbe. “African American Folklore.” Journal of Black Studies, vol. 27, no. 4, Mar. 1997, pp. 435–55, https://doi.org/10.1177/002193479702700401.

Thomas, Henry. Texas Worried Blues. 18 Dec. 1926,

Tracy, Steven C. “To the Tune of Those Weary Blues: The Influence of the Blues Tradition in Langston Hughes’s Blues Poems.” MELUS, vol. 8, no. 3, 1981, pp. 73–93, https://doi.org/10.2307/467538.

Trotter, Joe William. “The Great Migration.” OAH Magazine of History, vol. 17, no. 1, 2002, pp. 31–33. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/25163561. Accessed 4 May 2025.

I hope you enjoyed reading as much as I did writing.

With all I have,

Trixie.

I haven't even began reading, but my heart is doing the thing it only does when I read your work